Guest Post: Anna Winter - I am a Ballet Nerd

12.06.19

I am a ballet nerd. Later this month I’ll be scampering over to Sadler’s Wells to see Birmingham Royal Ballet. At the weekend I was there like an eager beaver in the stalls to watch San Francisco Ballet, before they return stateside. In August, the Bolshoi are coming to Covent Garden – spasiba Moscow! The capital’s upcoming dance calendar is like pungent catnip for balletomanes and bunheads.

But before I start rolling around on the laminate, purring and dribbling slightly at the prospect of watching Alexei Ratmansky’s version of Shostakovich’s Soviet comedy The Bright Stream, perhaps it’s time to address some issues for the ballet-averse or agnostic out there.

Because LET’S BE HONEST: ballet can be off-putting. It’s not in the mainstream. Access is improving, with cheap ticket deals and live cinema screenings, but chances are that you wouldn’t take a casual punt at the pictures on a three-act classic of a Tuesday evening if you don’t know much about it already. Ballet’s formalities – its codified language, traditions and tiaras – can understandably appear impenetrable, ludicrous or horribly conservative. What follows is a friendly blog designed to encourage the ballet-avoidant to set that aside and give it a go…

A theatre critic (garden variety male) once asked me with a slight smirk how I could like ballet and be a feminist at the same time. As if all art forms and just about every sphere of life isn’t infected by white patriarchy. Admittedly, ballet does have specific diversity issues. Most choreographers getting main stage commissions are still male. Most classical companies are largely white. Ballet’s aesthetic standards can be uncomfortable from a feminist perspective: the female dancer strives towards the appearance of weightlessness, rising up onto pointe or being lifted by a male partner. Contemporary dance emerged as a gravity-rooted reaction to the upward trajectory and upright carriage of classicism. But that doesn’t make ballet offensive or invalid. Pointework offers so much expressive possibility beyond the lightly fluttering bourrée (a run en pointe.) Yes, a dancer can appear impossibly graceful and floaty, but her feet can also jab and stab, explore, falter, or invoke authority. Choreographer Cathy Marston draws out character (often strong and mature female ones at that) using the physical language of feet.

In order to achieve these feats, a dancer must be incredibly strong as well as lean. Anyone who gets hoofed by a ballerina isn’t going to forget it in a hurry: as a recent article in The Guardian pointed out, most dancers at the Royal Ballet can lift 2.5 times their body weight using just their calf muscles.

Of course, this mega strength is often belied by the role a dancer portrays on stage. Many of the classical canon’s female characters have an inherent fragility. The principal roles are often princesses or teenagers or teenage princesses. You don’t find many mature single mothers tackling two jobs and an alimony dispute. So sometimes ballet can feel infantile or ingenue-obsessed. Why, you might ask, are all these grown adults prancing around pretending to be fairies? Why, when the world contains everyday horrors like Boris Johnson, corneal ulcers and TERFS, is this person sincerely trussed up in tulle and a tiara?

BUT – the broad strokes of myth and fairytale speak of life’s larger archetypes and primal fears. The Sleeping Beauty isn’t just a flimsy narrative about a royal brat’s Sweet 16 party that goes awry with an extremely minor stabbing. It’s a metaphor – for planetary order, for innocence and adulthood, for the passage of time. Ballet’s codified language and visual brilliance can evoke all this – and the more you see it, the more apparent it becomes.

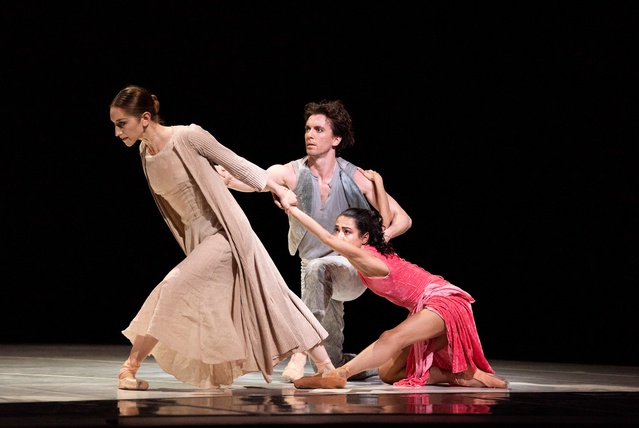

But if you want real flesh and blood, then there’s a choreographer like Kenneth MacMillan, whose neoclassical works explore the ecstatic passions and darkest recesses of human experience: madness, lust and death. Meanwhile, abstract works can allude so imaginatively to ambiguous palettes of mood and feeling, like the inscrutable serenity of Frederick Ashton’s Symphonic Variations, or the blithe physical poetry of Christopher Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour. The sheering lines and pliant plastique of ballet can suggest states that are sublime, numinous, beyond the verbal constrictions of language.

Finally, from the sublime to the ridiculous: the male dancer’s bulge. I admit that I do battle with the bulge. They are distracting and faintly amusing, if not downright hilarious, depending on my mood. Sometimes it’s a relief, for everyone involved, when the blokes get to ditch the white tights in favour of more skimming slacks, or even culottes. Nevertheless, the male appendage has got to go somewhere. I’d rather see it neatly marshalled by a dance belt (ballerino jock strap) than openly furtled with in a Tesco self-checkout queue, which is what I encountered about an hour ago while trying to buy cat treats and gnocchi. Now get me to Covent Garden!

Anna Winter is a freelance arts journalist and dance critic, writing for The Guardian, The Stage and Dance Gazette. @AnnaEWinter