At the Soane Museum

07.12.18

Our PR Director Elin has been taking an evening course in Creative Non Fiction writing at CityLit, which is just near the Mobius office. As part of her homework, she’s been doing some exploring in the local area. We thought it might be fun to share an essay she wrote on the Sir John Soane museum

How can a man’s desire to preserve the house he lived in - as it was - be so great that he passes a law to ensure it? That’s the question on my mind as I step into Lincoln’s Inn Field, damp leaves underfoot, on a crisp November afternoon. I have left behind a room of half-packed boxes, ready for another move (the fourth this year) to a new home I hope, this time, will have some permanency.

Putting aside the immense privilege and power you must be in possession of to make such a thing even possible, why would you do it? Sir John Soane, master architect of the early 19th century - grand designer of banks and of galleries, mason, collector of antiquities – is the man who did. By an Act of Parliament passed in 1833, Sir John decreed that his house and offices - also home to his enormous collection of artefacts from ancient civilisations - should on his death be bequeathed to the British nation ‘for the benefit of amateurs and students’ with no changes allowed from the way he left it.

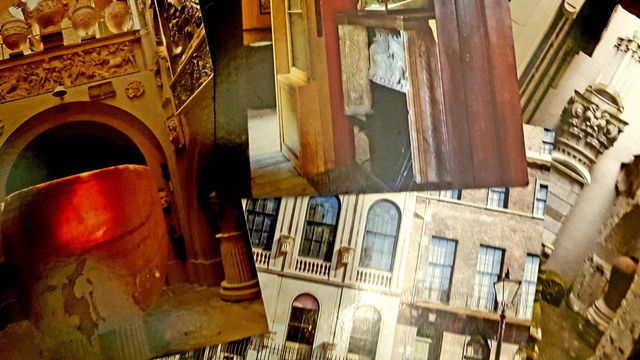

Walking up to the front door of the Soane Museum I comply with a request to turn off my phone completely and put my handbag inside a clear plastic bag to carry for the duration of my visit. Negotiating a path through a gift shop packed with tourists in damp raincoats, I pass down a narrow stone staircase, first through the plain and stony kitchen, and then onto the recently-restored catacombs which house most of Sir John’s collection.

Serried ranks of neoclassical treasures adorn each wall. Among the greys of ancient rocks my eye is drawn to a bright construction rendered in wood and plastic painted in black and white stripes and pieces picked out in neon. I wonder at the purpose of this alien object, surely in contravention of the famous Act? A children’s playcentre installed to placate 21st century families who visit? Rounding a corner I’m in a room doused in the heavy scent of wood (just as you feel a Victorian museum should be). A corner jumble of stony constructions brings to mind a suburban garden centre, touting water-spouting Jupiters and concrete-hewn nymphs to the upwardly mobile of perhaps, Surrey or Essex.

And then I find myself in the room that houses this building’s most famous artefact, the sarcophagus of Pharoah Seti, the grandest that had been found to date. It was purchased by Soane in 1824, the British Museum having turned it down for being a bit on the pricey side. Peering over the side, I expect to find a mummy. Or one of those gold body cast things. Yet it seems the great man’s desire for preserving of death wishes may not have extended to the inhabitant of this stone coffin -it’s empty. An avuncular guide talks a group of French tourists through the engravings on the casing and I look up through the narrow atrium, with its yellowed windows and rows of stony faces staring down. And I try to imagine the party I’ve heard took place (in this room) to celebrate the arrival of this most sought-after of artefacts. By all accounts a no-expense-spared three-day bender attended by the Prime Minister and all the cool kids of early 19th century society.

I spot another black-and-white-and-neon sculpture as I head for the stairs. What are these things? It won’t be long before my question is answered. Through a door at the far end of the first floor I spy a room with prints that echo the colour pallet of the sculptures – think rave tarot cards depicting masons and necromancers - and I wander in. A sprightly man approaches, suited and badged with the regalia of the museum.

“I was just wondering what these things are, in here, and I saw some around the building” I say.

“I often ask myself the same question” he says. “This is a gallery space where we invite contemporary artists to present work that responds to the collection here. But we’ve also recently refurbished the ceiling, take a look”

He gestures up to an ornate arrangement of plaster and glass picked out in pastels. Italianate, I might say, if I knew anything at all about it. In the middle of a room, there is a large book mounted on a stand and covered by a cloth. He uncovers it. I see the title page. It’s called Crude Hints Towards an History of My House in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

“Yeah, I’ve read about this, I say. “Why would you draw pictures of the buildings that were your life’s work in ruins.? It seems a bit weird”

“You’ve heard about it?”

“I’m a writer…there’s something I’m working on…I’ve been doing a bit of research” I say with a conviction that surprises me.

“Do you have ten or fifteen minutes?” he says “I can tell you something about the story”

I do.

He starts from the very beginning: John Soane has fairly humble beginnings as the son of a bricklayer from Berkshire. He scores an apprenticeship with George Dance, one of the top architects of the day and at some point goes on that 18th century Gap Year they called the Grand Tour where he was inspired (and hugely influenced by) the classical architecture he sees on his travels. In 1776 with a design apparently envisioned for Lambeth Bridge he named ‘A Bridge of Magnificence’ (and my guide calls “the Ponte Vecchio after LSD”) he wins the Royal Academy’s Gold Medal. You might have thought that would be his making but in fact, it took a little longer than that and he didn’t really crack it til he married Miss Eliza Smith in 1784. She was the love of his life but also brought a little family money. They had two children – John and George – born just a year apart - and John Senior was determined that they would carry on the family legacy and that the premises he’d built and maintained in Lincoln’s Inn Field would become the seat of a lasting dynasty of architecture. It’s not quite how it worked out, with older son John passing away at 37 from tuberculosis and George turning out to be a massive hedonist and gambler who ended up in debtors’ prison and afterwards wrote a pamphlet denouncing his father (perhaps the early 19th century equivalent of giving a Mail on Sunday exclusive) and broke both his parents’ hearts.

According to my guide, it’s at this point that Soane started thinking about alternative ways to preserve his legacy.

“But isn’t it a bit dark” I ask “To draw pictures of the buildings you created, your life’s work, in ruins?”

“I don’t think it is dark, he says, lifting the book’s cloth cover once more “I think he was very influenced by what he saw on his Grand Tour, all those ancient ruins that he saw and sketched.” It takes me a moment to process what he means.

“So in fact, when he was drawing the buildings he designed as ruins in the future he was imagining they would survive, like ancient temples, amphitheatres, like the acropolis or something, and be observed by the scholars of the day?”

“It wasn’t the only thing about the Tour which influenced the building” he said. “Look at this.”

Walking back into the atrium, we look back up at the yellow glass. “He put this in to replicate the Mediterranean light so students who had never seen what he had on the Tour could sketch under it”. Students of art and architecture still sketch here today, he tells me. There were some here just this morning. I’m on the point of leaving - I have to get back to the office. As we walk towards the exit, he gestures to a bust. It’s an imposing marble in full Roman Empire style. He explains that it was made by Sir Francis Chantrey, a leading artist of the era, who on delivering the sculpture to its owner said “I know not if this is Caesar or Soane, and nor do you.”

Indeed I don’t. I return home to my boxes of impermanent - and potentially unimportant - objects with more questions than I set out with. What really cemented the Act that created this museum? Hubris? Extreme narcissism? The insecurity of a man who made it from the bottom to the top and couldn’t lose it, even in death? Or an altruism that has ensured we still get into this museum for free?